This is the eighth post in a series about rebuilding the Magic Pages infrastructure. Previous posts: Rebuilding the Magic Pages Infrastructure in Public, The Townhouse in the Middle, Requirements First, Taking the Plunge, Swim, Docker, Swim!, The Calm After the Storm, The Rehearsal Stage.

In my last post, I showed you the rehearsal stage – thirteen VMs running on a Proxmox server in my office, mirroring the production architecture I'm building for Magic Pages. Three Ceph nodes. Three MySQL nodes. Three Swarm managers. Three workers.

(Well, in production, the numbers will be different, since there is a lot more workload to handle.)

But I skipped over something important: why that architecture? Why three separate tiers instead of cramming everything onto fewer, bigger machines?

The tempting answer to an architectural question like this is "hyperconverged."

It's a term that's been popular in enterprise infrastructure for years. The idea is simple: instead of having separate servers for storage and compute, you combine everything onto the same machines. Fewer servers. Simpler networking. One type of server to manage.

I seriously considered it. Three beefy servers running Ceph storage and Docker Swarm containers and the control plane. Everything in one place. Elegant, right?

But then I remembered why I was rebuilding this infrastructure in the first place.

The Longhorn disaster taught me something about blast radius – and the Longhorn setup was, in fact hyperconverged (storage and compute on the same servers).

When Longhorn's storage layer started failing, it didn't just affect storage. The storage processes were consuming CPU on the same machines running containers. When storage got overwhelmed, the Ghost sites got starved. When the Ghost sites failed health checks, Kubernetes tried to reschedule them, which hit storage even harder. The whole thing cascaded.

In infrastructure terms, this is called "blast radius" – how far does damage spread when something goes wrong? With hyperconverged systems, the blast radius is... everything. A storage problem becomes a compute problem becomes a networking problem. All on the same machine.

This isn't a novel observation. But I guess, every developer has to experience it one way or another to understand it 🙃

So I drew lines instead.

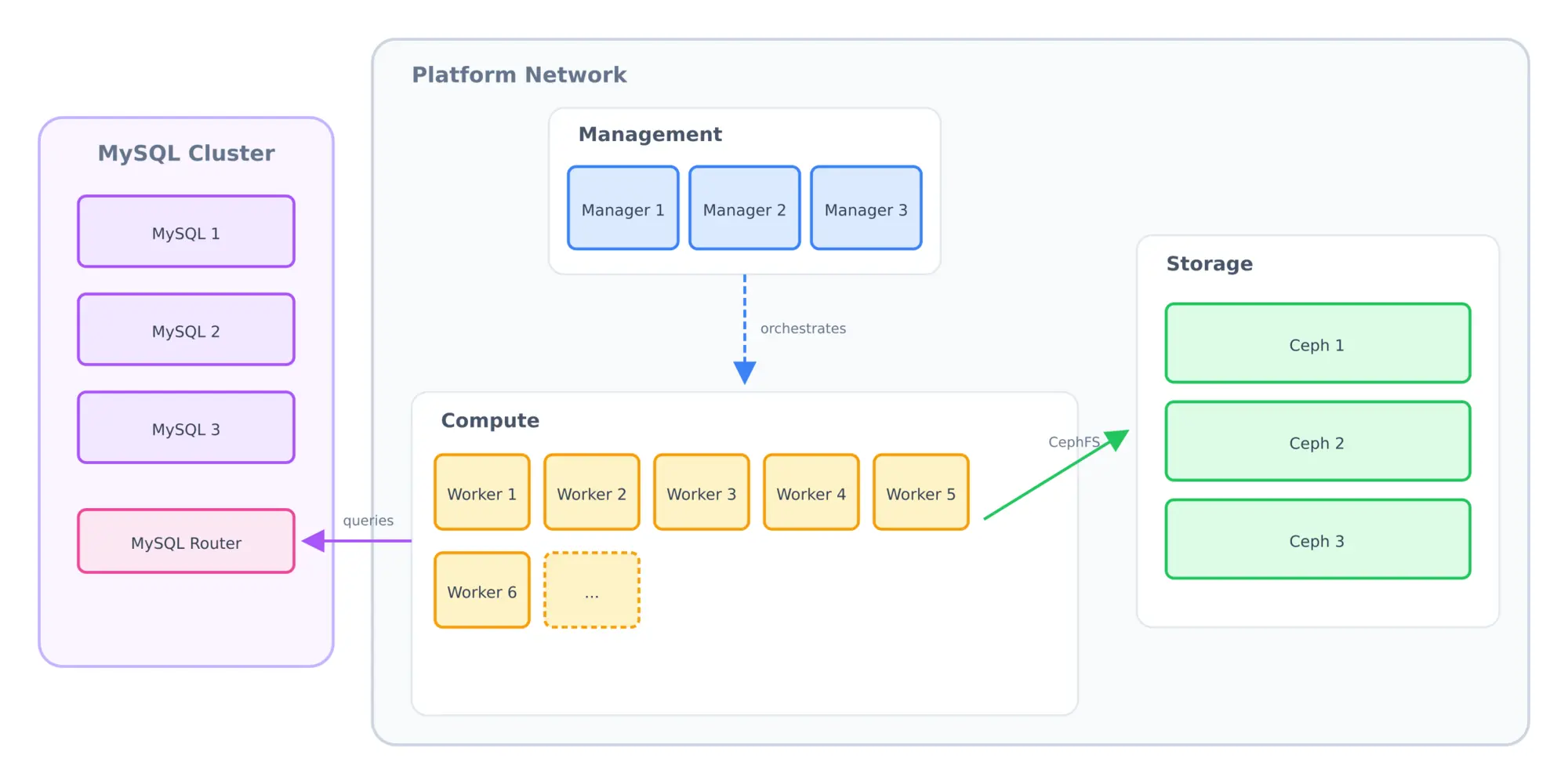

Three tiers, completely separate:

Management

These are small VMs that do exactly one thing – run the Docker Swarm control plane. They hold the cluster's encryption keys and secrets. They schedule containers. They don't run any customer workloads.

This isn't my idea. Docker's own documentation:

You should isolate managers in your swarm from processes that might block swarm operations like swarm heartbeat or leader elections.

Storage

Dedicated servers running Ceph and nothing else. All they do is store data and serve it to the compute nodes. No containers competing for RAM. No customer traffic touching these machines.

Ceph has proven itself as a robust storage solution over the last 6 months or so in this exact setup. Compared to NFS or Longhorn it was butter smooth to manage it.

And while Ceph is providing storage over network, latency is so marginal that I have never noticed it. Having all servers in the same data center is essential here (yes, single point of failure – but you'd have the same problem for hyperconverged servers).

Compute

These are pure Docker Swarm workers. Their entire job is running Ghost containers. They mount the Ceph storage over the network, but they don't participate in storage operations. All of their RAM is available for customer sites.

And here's what this separation buys me:

Smaller blast radius. If a container escapes its sandbox (container breakouts are rare but possible), it lands on a worker node that has no access to cluster secrets. The management tier is a separate machine entirely.

Independent failure domains. If Ceph has a bad day, the storage tier degrades – but the control plane keeps running. I can still inspect the cluster, drain nodes, and make decisions. With hyperconverged, a storage hiccup can freeze the entire cluster. Been there, done that.

Independent scaling. Need more compute? Add workers. Need more storage? Add more capacity in the Ceph cluster. With hyperconverged servers, you have a bit of a problem: if you need more storage, you're also buying more compute whether you need it or not.

Clearer debugging. When something breaks at 2am, you want to know which box to SSH into. Is it storage? Check the storage tier. Is it a container? Check the workers. Is it scheduling? Check the managers. Separation of concerns isn't just a software principle – it applies to infrastructure too.

My biggest surprise: this ended up being cheaper than hyperconverged.

I expected more machines to mean more money. But hyperconverged servers have hidden overhead. Every node running Ceph storage needs extra RAM and CPU for the storage daemons – resources you can't use for actual workloads. When I ran the numbers, dedicated tiers with right-sized machines came out ahead.

The management tier is especially cheap – these are just control plane processes, which need almost no resources. Small cloud VMs work perfectly.

Here's what the architecture looks like (in a somewhat simplified way):

An uneven number (because of quorum) of managers. An uneven number of storage nodes. Multiple workers (however many the workload requires).

Each tier can fail independently. Each tier can scale independently. Each tier has one job.

Looking at it with some distance...this is not exciting. It's not novel. It's exactly what Docker's documentation recommends, what every infrastructure veteran will tell you.

And we're back at one simple fact: the boring answer is probably the right answer.