This is the seventh post in a series about rebuilding the Magic Pages infrastructure. Previous posts: Rebuilding the Magic Pages Infrastructure in Public, The Townhouse in the Middle, Requirements First, Taking the Plunge, Swim, Docker, Swim!, The Calm After the Storm.

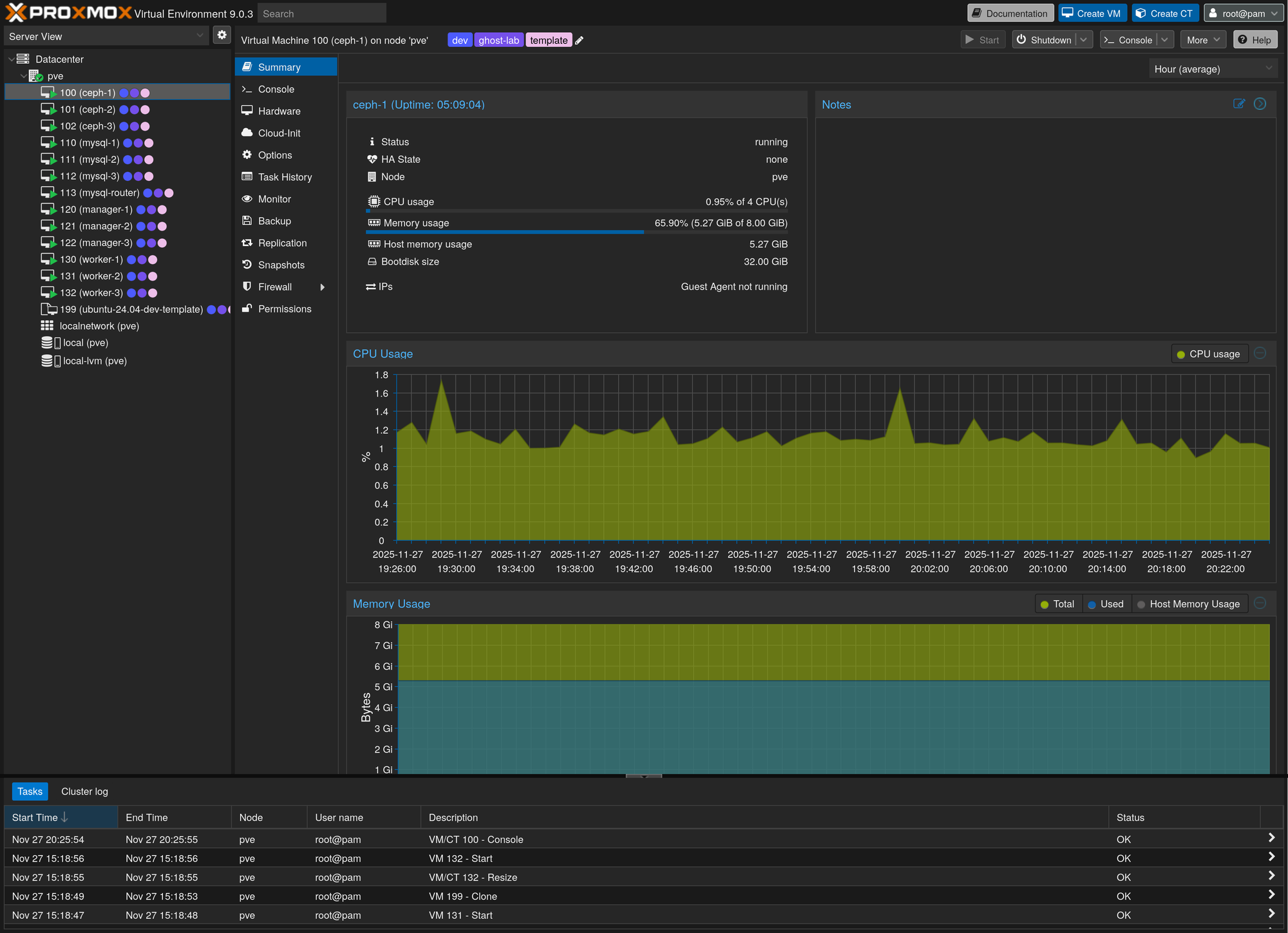

It's a cold, snowy November day, and I'm staring at a Proxmox dashboard showing thirteen virtual machines humming away on a single server, in a new server rack in my home office. Three Ceph nodes. Three MySQL nodes. Three Docker Swarm managers. Three workers. A MySQL router. All running on hardware that cost less than a month's worth of Kubernetes cloud bills.

This is my rehearsal stage.

If you've been following along for a bit, you know that I have thought a lot about re-doing the Magic Pages infrastructure. I don't want to bore you with a ton of links (they are on top though), however, here's a key piece of the puzzle:

After a regular Ghost update, Longhorn, the storage engine I had been using back then, took down a subset of the Ghost sites on Magic Pages – the final straw for me to switch from Longhorn to Ceph, even though the internet is full of stories about how complicated Ceph actually is.

But something shifted after I deployed Ceph and things finally stabilized. For the first time in months, I had headspace to think beyond the next fire. The switch to Ceph was the best thing that could have happened. Since then, things have been calm.

I realised that – so far – every major infrastructure decision I made in the past 2-3 years was reactive. Something broke, I scrambled to fix it. Something scaled badly, I threw more resources at it. I was always responding to problems, never preventing them.

So, before diving into rebuilding the entire infrastructure for Magic Pages, I asked myself: what if I could test infrastructure changes before they hit production?

The idea isn't revolutionary. Developers have had staging environments forever. CI/CD pipelines run tests before deployments. But for infrastructure itself – the actual servers, the storage clusters, the networking – most people I know don't have a 1:1 replication to test on.

For Magic Pages, I had a few smaller test servers running, but nothing that fully simulated my production environment. Databases, storage, application runners – all separate, all incomplete.

Then, in late summer, I had a bit of cash left over after one of the most successful months in Magic Pages history. So... what if I built a miniature copy of my production environment?

Not a scaled-down approximation. Not a single-node "development" setup that has no resemblance to reality. I needed the full architecture to test it from all angles. The three-node Ceph quorum, the MySQL cluster with failover, the (future) Docker Swarm managers maintaining consensus – just... a bit smaller.

The thing about infrastructure is that problems aren't (usually) about scale. They're about topology. A three-node Ceph cluster with 8GB VMs will expose the same quorum issues, replication failures, and split-brain scenarios as one running on 64GB dedicated servers. The failures are identical. Only the capacity is different.

So that's what I built.

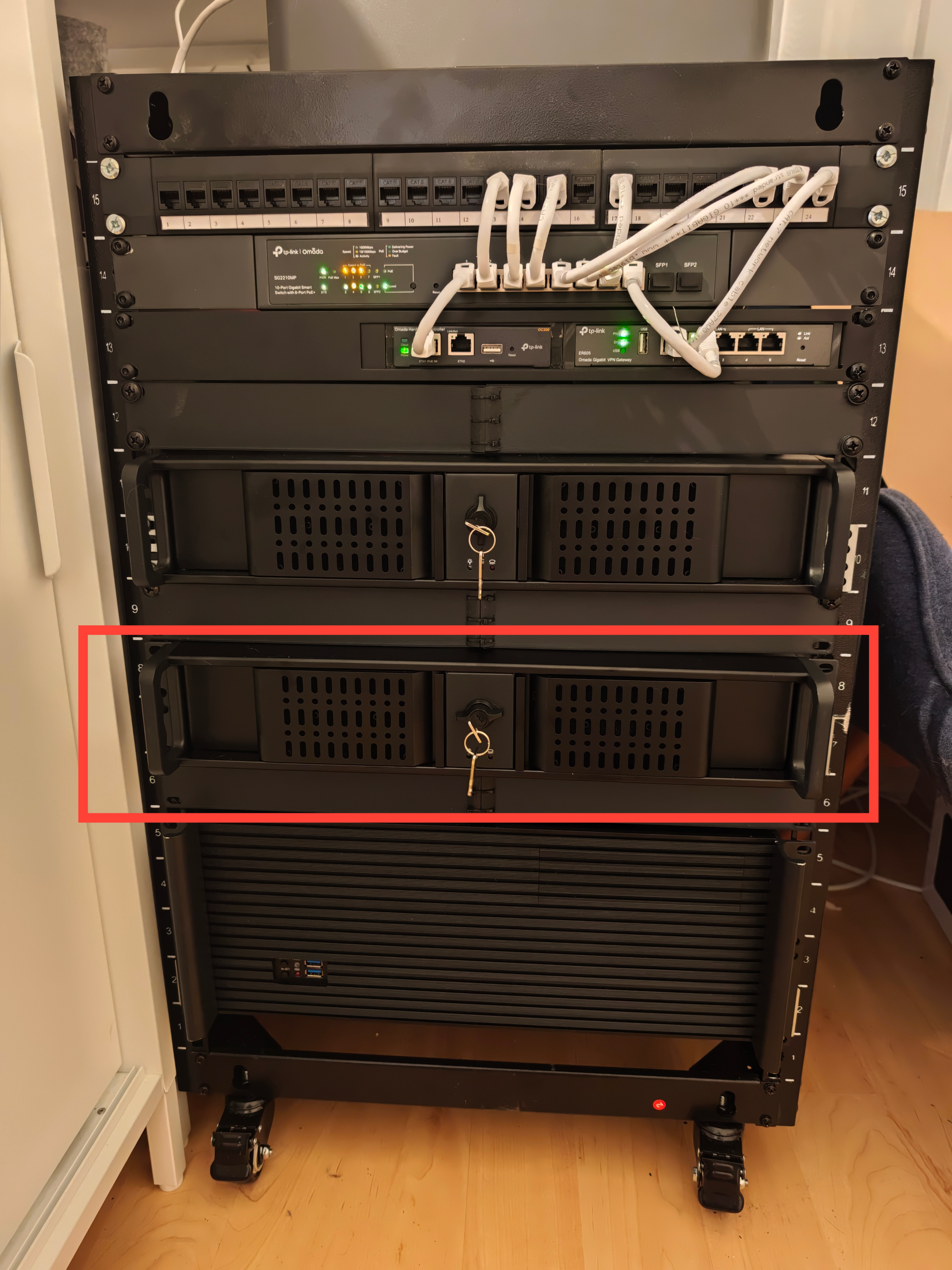

That middle server – my new rehearsal stage – is a Proxmox server that's pretty maxed out for what you can get in this form factor: an AMD Ryzen 9 9950X with 16 cores, 128GB RAM, and lots of quiet fans to keep things cool.

The 9950X might be overkill. In fact, the 128GB RAM is too. However, I wanted a server that could last for a couple of years. Something I could use to fully simulate my production environment, no matter how it grows.

Right now, it's running:

- A full Ceph cluster (3 nodes)

- A full MySQL cluster (3 nodes)

- A MySQL Router instance proxying the MySQL cluster

- 3 Docker Swarm managers

- 3 Docker Swarm workers

But, the real magic isn't in the VMs themselves. It's in how they're created.

I use OpenTofu to provision the VMs on Proxmox. It's a tool that essentially lets me write a few lines of code ("this is what I want"), and boom – thirteen virtual servers are created.

Then Ansible takes over. Ansible is another popular tool for defining infrastructure as code (IaC). There, I don't define how the servers themselves should look, but what I want them to run. I describe my ideal situation, and Ansible makes sure everything's installed properly on the servers (so-called "roles" and "playbooks").

The same Ansible roles that will eventually configure the new production environment are configuring the testing VMs. The only difference is the "inventory" file – a file that tells Ansible whether it's talking to my Proxmox VMs in the corner of my office, or to servers in Hetzner's data centers.

This is the part that makes me weirdly... happy. When I write a new Ansible role for, say, configuring Ceph mount options, I can test it on VMs that I can destroy and rebuild in minutes. If I break something catastrophically – and I have, multiple times – I just run tofu destroy and start fresh.

There's a certain irony here. I spent months fighting complex infrastructure – Kubernetes operators, Longhorn replication, Helm chart dependencies – only to arrive at something almost embarrassingly straightforward.

Create VMs, install things on them, test, deploy to production, repeat.

It feels almost too simple. Which, I've learned, usually means it's exactly right.

Next up: putting this rehearsal stage to use and building out the actual production architecture.